'Moneywall' could be baseball's next frontier

The Kansas City Royals just revealed a whole new type of analytics for teams to exploit. Why isn't this more common?

Welcome back to Club Sportico, where we break down the intersection of sports and money—with an extra bit of humor and opinion. Today, we’re talking about architecture. And wind patterns. And fly ball rate.

Earlier this week the Kansas City Royals made a change that they said would produce more wins for the upcoming season. It wasn’t a free agent signing, a trade or any other roster change. It didn’t involve the team’s equipment, its coaching staff or its front office.

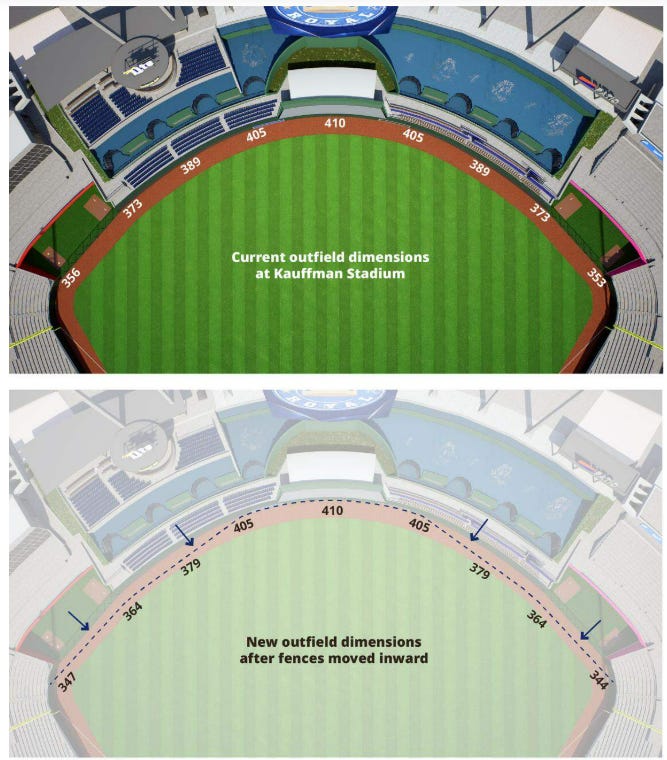

Instead, the big to-do was about engineering. The Royals said they would alter the layout of Kauffman Stadium, moving in the outfield walls in both left and right field, and lowering the fence by 18” in most places. I’d typically ignore an an announcement like that, but I was fascinated by how the Royals talked about the decision.

“During the course of the season, we just started doing some research, running some numbers and trying to figure out how much this really impacts our offense,” general manager J.J. Picollo said. “Consequently, how would it affect our pitching staff? Ultimately, we concluded that we would be a better team offensively. With our current pitching staff, the changes in the dimensions wouldn't impact negatively as much as it impacts our offense positively."

I won’t lay out all the specifics—here are two good stories if you’re curious—but in short, Kauffman Stadium is notoriously unfriendly to sluggers, and after years of watching well-hit balls caught on the warning track, Picollo asked Royals owner John Sherman for permission to explore a change. He then asked assistant GM Daniel Mack, who has a Ph.D. in computer science and a master’s degree with a concentration in machine learning, to crunch as many numbers as possible.

Mack assigned a run value to every fly ball hit in Kauffman, then layered on the team’s current roster of hitters, its pitchers, its opponents, the wind patterns, and even the stadium’s altitude1. He then played with distances and fence heights that would not only play around the league average, but also give this current Royals team an advantage.

Here are a few relevant stats: Royals pitchers last year induced soft contact 17.3% of the time, the highest rate in baseball. The staff’s hard contact rate (31.7%) was the seventh lowest in the league. Kansas City’s fly ball rate was sixth. Those numbers imply a group that is surrendering fewer deep fly balls than the average team.

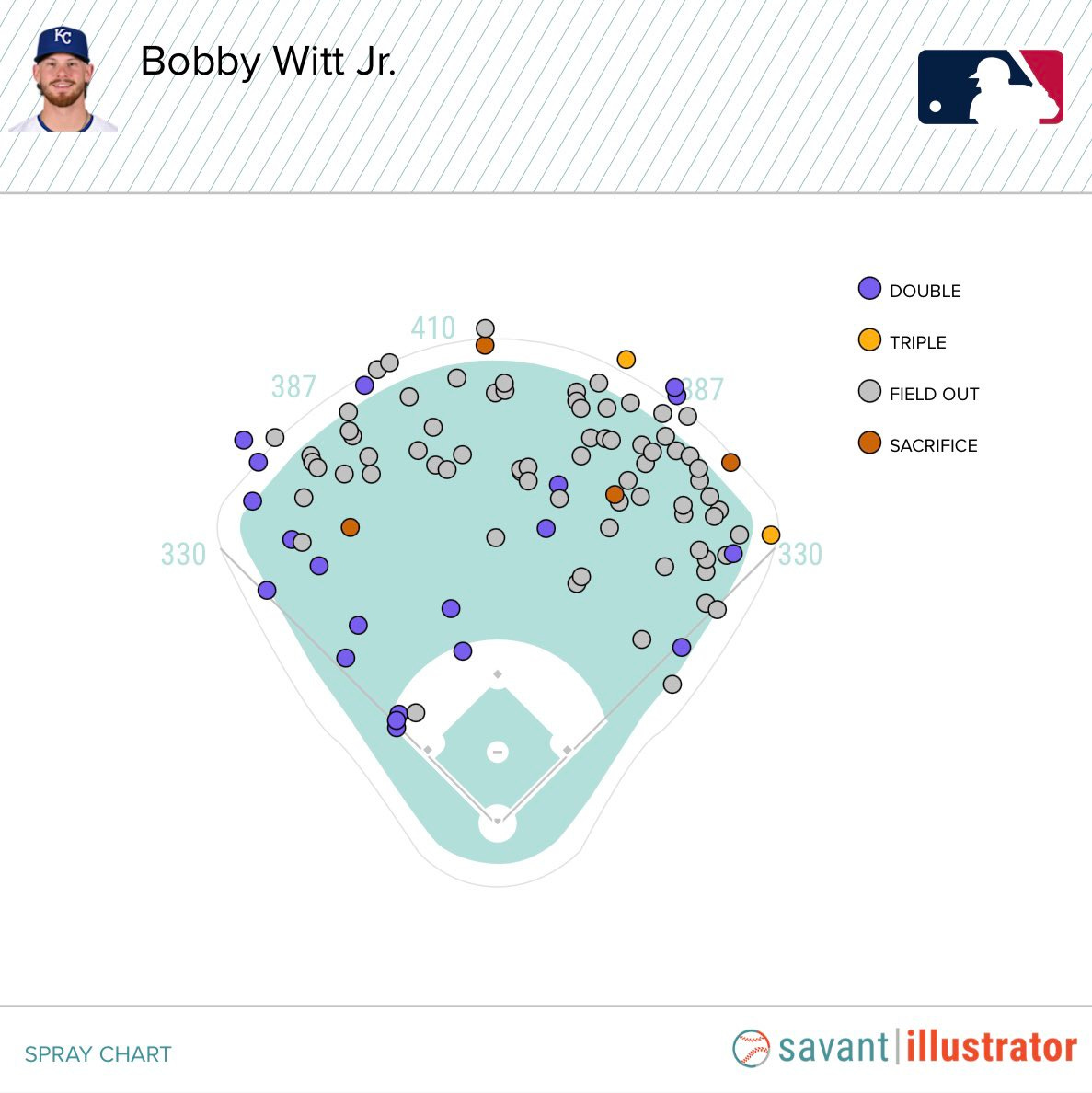

On offense, Royals teams have typically been built around contact hitters and speed—necessities given the cavernous home stadium—but 25-year-old star shortstop Bobby Witt Jr. has pop, as does first baseman Vinnie Pasquantino and a few of their biggest prospects. Look at Witt’s spray chart of line drives and fly balls at home last season. You can see the impact this might have.

Moving forward, Mack says the team no longer needs to build its roster specially for the sport’s second-largest outfield.

“That’s just chasing lightning,” Mack told the Kansas City Star. “I don’t think that’s smart in general. It’s certainly not smart for a smaller-market team that needs to be adaptable to the personnel that you can acquire.”

All of this results in what the team believes will be worth an additional 1.5 wins next season. And in the analytics-heavy world of baseball, that’s a lot! Teams make bigger decisions based off much smaller margins.

It got us talking in the Club Sportico clubhouse about why we don’t see this more often. Young stars like Witt are increasingly signing long-term deals that lock them into teams for a decade or more2 and clubs definitely understand the various ways in which outfield dimensions impact players. The Orioles made Camden Yards more pitcher-friendly three years ago in a move that appeared aimed—at least in part—at neutralizing Yankees slugger Aaron Judge, who may play there 10 times per year for the next decade. In response, Judge called it a “travesty” and a “Create-A-Park.”3

So what’s to stop a team from looking at its roster every offseason and making tweaks to their fences? Or more dramatically, what’s to stop a team from putting its outfield wall on tracks and moving it based on who’s in town, which way the wind is blowing, or who is starting on the mound?

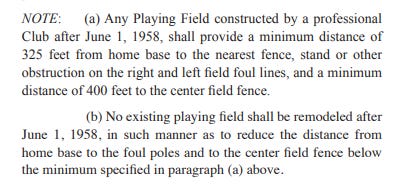

The answer, technically, is nothing (!). Major League Baseball’s 191-page rule book is light on guidelines for the dimensions of the outfield. The centerfield wall must be at least 400 feet from the plate, and the rest of the outfield wall must be at least 325 feet. That’s for venues built after 1958, which allows stadiums like Fenway Park to get away with its 302-foot right field fence.

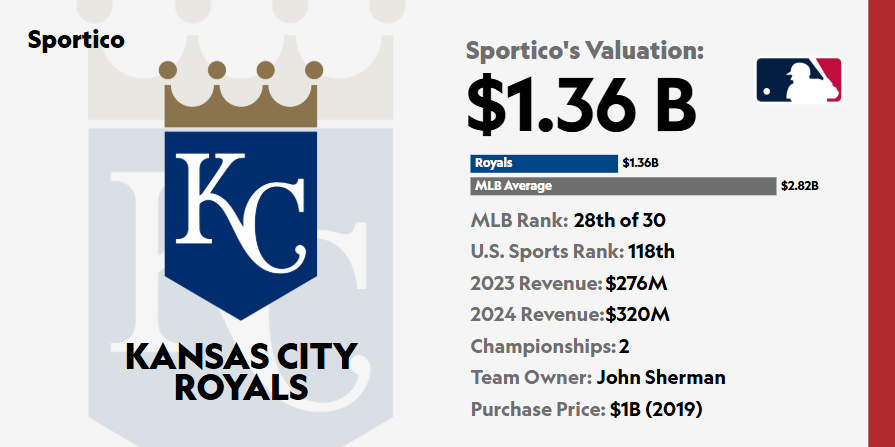

According to someone familiar with the broader league bylaws, MLB has no limit on the number of times you can make changes (more on that later). That said, there are a few reasons you might not see a rush of alterations at ballparks across America. The biggest one—of course—involves money. Construction isn’t cheap, of course, but neither are the tickets that sit right up against the outfield walls.

In addition to helping the team on the field, the Royals’ move will add about 230 seats in Kaufman’s left and right field seating areas4. If we assume for a moment that those tickets cost $80 each, that’s an additional $1.5 million in sales annually for the team (before accounting for the extra beer volume). For reference, Royals revenue in 2024 was $320 million.

If there’s any team for whom cost would be irrelevant, it’s the Mets.5 And billionaire owner Steve Cohen moved Citi Field’s fences in three years ago, but that move wasn’t about on-field play6. It allowed the team to build out a new club area with living room-style seats and personal TVs.

Another challenge, according to people who evaluate talent for a living, is the inexact science of the math. Rosters change constantly, for the home team and the visitor. What’s good for your left-handed slugger is also likely good for the left-handed slugger on your division rival. There’s just a whole lot of variables at play.7

Lastly, and maybe most importantly, is MLB itself. Yes, there are no rules in place about how often a team can move its fences, but there is a process. And it’s not instantaneous. Every year MLB asks teams to provide plans to any changes to the field, fences, clubhouses or batting cages. The league then reviews the plan.

I asked a baseball source if a team could put its outfield on tracks for easier movement. The person said “it’s likely” it wouldn’t be approved, and that the expectation is that modifications don’t become an annual thing.

Womp womp womp. I know, I’m bummed also. But I’m here for Moneywall regardless. I want a rich, progressive owner to try it. And I’m looking at you, Mark Attanasio.

Jacob’s ⚡Take: Maybe the Cowboys should hire Daniel Mack to run the numbers on the potential impact of some curtains…

On the most recent Sporticast episode, Eben and Scott were joined by Kurt Badenhausen to discuss the highest-paid athletes in the world. He dropped a hot take on Victor Wembanyama’s earning potential 👇

Club Sportico is a community organized by Sportico, a digital media company launched in 2020 to cover the business side of sports. You can read breaking news, smart analysis, and in-depth features from Eben, Jacob and their colleagues at Sportico.com, and listen to the Sporticast podcast wherever you get your audio. Contact us at club@sportico.com.

Kauffman Stadium has the fifth highest altitude of any MLB venue?? The more you know.

In 2024, after just two MLB seasons, Witt signed an 11-year deal with the Royals worth $288.7 million.

Before the 2025 season, the Orioles remodeled again.

That’s 150 seats in left field and another 80 “drink-rail” seats in right field.

And the Dodgers, of course, who instead invested in new toilets as a way to woo a coveted free agent.

Two prior changes to the dimensions at Citi Field were about play on the field, but weren’t pitched as something tailored to the Mets roster.

Interestingly, I learned this week that one of the challenges of evaluating players in Asia is that most parks there are much smaller, which impacts many of the metrics used to assess how that player might perform in MLB.

Moving in the walls helps the hitters but also provides room for more seats or potentially new premium seating areas, which increases ticket revenue. It could be a rare baseball/business team win-win!